|

|

Greatest Space Events of the 20th Century

In this series of five articles, space.com takes a decade-by-decade look at the 20th century's most significant developments in space.

By Andrew Chaikin, Executive Editor, Space and Science,

and Anatoly Zak

Eric Hartwell

contributed additional pictures and captions,

collated, and reformatted these articles.

|

|

|

Greatest Space Events of the 20th Century: The Fifties

By Andrew Chaikin,

space.com Executive Editor, Space and Science

posted: 11:33 am EST 27 December, 1999

When you think of the 1950s, you might recall the decade's contributions to popular

culture: Rock n' Roll, hula hoops, and horror films featuring a menagerie of giant

radioactive beasts. Long after Godzilla is forgotten, however, the fifties will be

remembered as the dawn of the space age.

When you think of the 1950s, you might recall the decade's contributions to popular

culture: Rock n' Roll, hula hoops, and horror films featuring a menagerie of giant

radioactive beasts. Long after Godzilla is forgotten, however, the fifties will be

remembered as the dawn of the space age.

For space exploration, the fifties were a time when fantasy changed to reality. At the

start of the decade, space travel was something that existed only in the pages of science

fiction, the kind of thing most people didn't talk about in serious tones. By its end, a

newly-created U.S. space agency was selecting pilots for real space voyages.

|

|

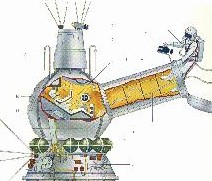

Von Braun's three-stage manned rocket with winged

glider for landing, and 250-foot-diameter space station.

Spacecraft for the moon landing (unstreamlined

to operate solely in the vacuum of space),

to be assembled in orbit nearby

|

A Cold War Quest

At first glance, it might seem that inspiration -- a love of exploration, a

fascination with the unknown -- was at the heart of this dramatic change. And it is

true that the fifties were ripe with inspiring writings about worlds beyond. A series

of articles in Colliers magazine, beginning in 1952, offered fantastic visions

of humanity's future in space, written by experts in the field and illustrated with

stunning works by such artists as Chesley Bonestell and Fred Freeman. The opening

installment in the Colliers series declared, "Man Will Conquer Space Soon."

Such presentations served to raise the American public's awareness that such things

were going to happen -- but would they happen as quickly as Colliers promised?

In 1952, no one would have guessed that only five years remained before the first Earth

satellite would be launched, and only seven before the nation's first astronauts would

be named. The reason those developments came as soon as they did -- and the force behind

the fifties' push into space -- was the Cold War.

The years after World War 2 were marked by growing tensions between the United States

and the Soviet Union. Soon after the war ended, both sides engineers who knew how to build

large, liquid-fueled rockets. And the U.S. monopoly on nuclear weapons ended in 1949, when

the Soviets tested their first atomic bomb. By the early 1950s, the U.S. and

U.S.S.R. were working to merge these technologies in a terrible new weapon, the

Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM).

|

|

R-7 - Credit: © Mark Wade.

|

Until very recently, most historians believed the Soviets got there first.

A brilliant engineer named Sergei Korolev led the Soviet ICBM effort, and his team

created a powerful new booster, officially designated R-7, but known to Korolev's team

by its Russian nickname Semyorka ("number seven"). It stood almost 100 feet high

and developed 880,000 pounds of thrust at liftoff. In August 1957, Semyorka flew

to its full range of almost 4,000 miles (2480 kilometers) -- enough to qualify it as an

intercontinental rocket. But the dummy warhead at the rocket's nose was destroyed during

reentry into the Earth's atmosphere. The Soviets made no mention of mishap in their

public statements. However, such problems would continue to plague the Russian ICBM

effort until December 1959, when the R-7 was declared an operational weapon. The

Americans, meanwhile, made a successful test of their own ICBM, called Atlas, in late 1958.

The Space Race Begins

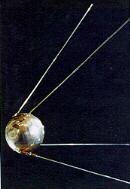

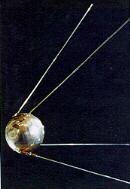

The ICBM was only part of Korolev's efforts. Korolev had bigger dreams: He wanted to

explore space. Under Korolev's direction, Semyorka was became the world's first

satellite launcher. On October 4, 1957, it sent the first satellite, Sputnik, into orbit.

|

|

Sputnik 1

|

Sputnik's bleeping electronic cry, heard by amateur radio operators around the world,

announced that the Soviets had scored not only a scientific achievement, but a strategic

one. If they could put a satellite in orbit -- and especially the 1,121-pound

(2,466-kilogram) Sptunik 2, which carried the first space passenger, a dog, in November

1957 -- then they could loft a nuclear warhead into orbit, where it could threaten any

American city. This was already clear after the R-7's test launch in August, but it was

only after Sputnik that the American public took the threat seriously.

|

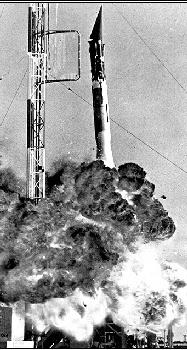

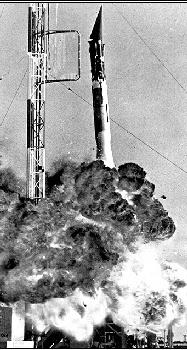

The explosion of Vanguard in

America's first launch attempt

|

|

Spurred in part by the public and media reactions to Sputnik, which bordered on

hysteria, U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower stepped up plans for the first U.S.

satellite, which had been scheduled for launch as part of the 1958 International

Geophysical Year. The first attempt, using a booster called Vanguard, ended in

failure on December 6, 1957; the rocket rose only a few feet, then sank back to Earth

and exploded.

|

|

The far side of the moon,

as photographed by the

Soviet Luna 3 probe in

October, 1959. |

Now hope rested with the U.S. Army's rocket team, headed by Wernher von Braun, who

had led the development of the V-2 missile in Nazi Germany. Von Braun's rocket, called

Jupiter C, successfully launched Explorer 1 on January 31, 1958. The U.S. had joined

the "space race."

But the Soviets held the lead. In January 1959, after several launch failures, they

fired a small probe, called Luna 1, past the moon, missing it by about 3,100 miles

(5,000 kilometers). Then, just past midnight, Moscow time, on September 14, the Soviets'

Luna 2 struck the lunar surface, becoming the first artificial object to reach another

celestial body. And in early October, Luna 3 swung around the moon and sent back the

first pictures of its hidden face.

The Americans, meanwhile, suffered a series of embarrassing failures with their

Pioneer spacecraft, which were designed to explore the moon's environment. Most failed

to escape Earth orbit; more than one blew up before reaching space. Pioneer 4, launched

in March 1959, was able to achieve lunar distance, missing the moon by 37,500 miles

(60,500 kilometers).

|

|

The dog Laika was launched

aboard Sputnik 2 to become

history's first space passenger.

|

Bigger Things Ahead

Even as the two superpowers lobbed robotic spacecraft at the moon, the space race

was becoming an even higher-stakes game. In April 1959 seven pilots were selected by

the newly created National Aeronautics and Space Administration as astronauts for

Project Mercury, the U.S. effort to put a man in orbit.

The Soviets, meanwhile, were training their own crop of space fliers, called

cosmonauts, who also hoped to be the first into space.

In the coming decade, astronauts and cosmonauts would set their sights on historic

journeys in space -- not only into Earth orbit, but to the moon.

Anatoly Zak and Eric Hartwell contributed to this article.

Timetable of Space Events: 1950s

|

Missions |

|

Achievement |

Country |

Spacecraft |

Launch Date |

|

First successful test of ICBM |

Soviet Union |

R-7 rocket |

August 21, 1957 |

|

First Earth satellite |

Soviet Union |

Sputnik |

October 4, 1957 |

|

First animal in space (the dog

Laika) |

Soviet Union |

Sputnik 2 |

November 3, 1957 |

|

First U.S. Satellite |

United States |

Explorer 1 |

January 31, 1958 |

|

First spacecraft to reach lunar distance |

Soviet Union |

Luna 1 |

January 2, 1959 |

|

First spacecraft to strike moon |

Soviet Union |

Luna 2 |

September 12, 1959 |

|

First photographs of lunar far side |

Soviet Union |

Luna 3 |

October 4, 1959 |

http://www.space.com/spacehistory/greatest_space_events_1950s.html

Copyright ©1999 space.com, inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Greatest Space Events of the 20th Century: The Sixties

By Andrew Chaikin,

space.com Executive Editor, Space and Science

posted: 05:05 pm EST 27 December 1999

|

|

The Vostok 1 launch of the first

man in space,Yuri Gagarin

|

For America, the 1960s begin on an anxious note. Many in the U.S. feared the

nation was lagging dangerously behind the Soviet Union in development of

Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs). In reality, secret photos from

American spy satellites were about to confirm what high-flying aircraft had

already shown: the so-called missile gap was not real.

But the Eisenhower administration could not reveal this knowledge to the

public, and in 1960 John Kennedy won the presidency over Eisenhower's Vice

President, Richard Nixon, partly on the strength of his stance on the missile

gap.

When it came to space exploration, no one could be sure how much Kennedy

would improve on his predecessor's lukewarm attitude. Within months after

entering office, however, Kennedy had no choice but to focus on human

spaceflight.

On April 12, 1961, the Soviets launched a 27-year-old fighter pilot named

Yuri Gagarin on the world's first piloted space mission. In his spacecraft

Vostok ("east"), launched atop a converted R-7 missile, Gagarin made

a single orbit of the Earth, returning 108 minutes after liftoff.

The Soviets did not reveal that the Vostok had suffered a malfunction prior

to reentry that almost killed Gagarin. When the cosmonaut returned unharmed and

exhilarated by his flight, the Soviet Union had scored another key space

victory.

Kennedy Reacts

For the young American president, Gagarin's flight came as a serious blow.

In Kennedy's mind, competition with the Soviets in space had become vital to

U.S. international prestige. On May 5, a former Navy test-pilot named Alan

Shepard -- judged by many to be the best pilot among the Original Seven

astronauts -- became the first American in space.

|

|

Alan Shepard inside his Mercury capsule, ready for launch.

|

Inside his tiny Mercury spacecraft, which he named Freedom 7, Shepard

rode a Redstone booster on a 15-minute suborbital flight. The nation reacted to

Shepard's feat with wild enthusiasm, and Kennedy took notice.

Kennedy had already been thinking about how to pull ahead of the Soviets in

space. He'd asked his advisors to come up with a project that would give the

U.S. a clear victory.

Less than three weeks after Shepard's flight, speaking before a joint

session of Congress, Kennedy made an announcement that would have seemed

unthinkable just years before: "I believe this nation should commit itself

to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon

and returning him safely to the Earth."

Many who heard these words -- including some at NASA -- wondered if

Kennedy's challenge was realistic. (A few even wondered if Kennedy had lost his

senses.) But it didn't take long for the space agency to begin figuring out how

to achieve it.

Meanwhile, the space race sped onward with ever more ambitious flights.

John Glenn -- the astronaut who seemed to step most easily into the role of

American hero -- became the first American to orbit the Earth on February 12,

1962. Inside his Friendship 7 spacecraft Glenn circled the globe three

times, marveling at the beauty of orbital sunrises and sunsets before sweating

through a fiery reentry into the Earth's atmosphere.

Three more astronauts followed Glenn into orbit; in May 1963 the sixth and

last piloted Mercury mission saw Gordon Cooper spending more than a day in

space.

|

|

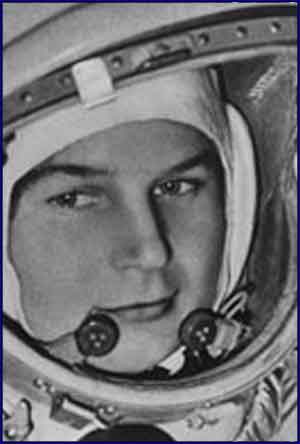

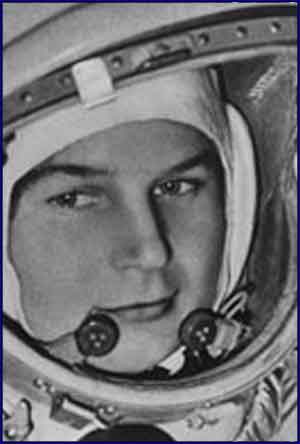

Valentina Tereshkova, first

woman in space, in 1963.

|

As important as these missions were for the U.S. program, they were

overshadowed by the Soviet Vostok flights. Cosmonaut Gherman Titov made the

first day-long flight in 1962. Andriyan Nikolayev in Vostok 3 and Pavel

Popovich in Vostok 4 staged the first dual space flight in 1963. Also in 1963,

a former cotton mill worker and parachute jumper named Valentina Tereskhkova

became the first woman in space, logging almost 3 days in Vostok 6.

And the Soviet firsts didn't end there. Under pressure from Soviet premier

Nikita Kruschchev, chief space designer Sergei Korolev staged another orbital

"spectacular." The Americans were planning their two-man Gemini

flights, but Korolev upstaged Gemini's planned debut by launching three

cosmonauts in a "new" spacecraft called Voskhod ("sunrise").

In reality, Voskhod 1 was nothing more than a converted Vostok. Only by

taking the dangerous step of denying the cosmonauts ejection seats and space

suits was Korolev able to achieve the feat. Fortunately, Voskhod 1 flew without

mishap.

But that wasn't true for the Voskhod 2 team of Pavel Belyayev and Alexei

Leonov, who made their day-long mission in March, 1965.

Early in the flight, a space-suited Leonov wriggled into a narrow,

inflatable airlock attached to the Voskhod's cabin, leaving Belyayev to pilot

the ship. Leonov then emerged into the void and spent several minutes floating

free, in history's first space walk.

|

|

When Leonov returned from his historic 1965 spacewalk, he found

he couldn't fit back in the hatch. (AP File Photo). No good quality

pictures are available because the outside camera could not be

retrieved from the airlock, which was ejected before re-entry.

|

Leonov almost didn't live to tell the tale: In the vacuum of space his suit

ballooned dangerously, making it almost impossible for him to get back inside.

Only by releasing some of his suit's air -- an almost desperate measure,

considering the risk of decompression sickness -- was the exhausted cosmonaut

able to re-enter the cabin.

Once again, the world was not told of these difficulties, and Leonov's feat

seemed to leave the U.S. program in the dust. But it would not be long before

the Americans caught up.

A Bridge to the Moon

Even as the Soviets racked up one space first after another, NASA was

getting closer to the first piloted Gemini missions. Launched by a converted

Titan 2 missile, Gemini was the most sophisticated spacecraft yet created.

Gemini astronauts would utilize an onboard computer. And they would be able to

change their orbit -- something no Soviet crew had yet accomplished.

For NASA, Gemini would serve as a bridge between the relatively simple

Mercury flights and the awesome challenge of the Apollo moon program.

In just 20 short months between March 1965 and November 1966, 10 Gemini

crews pioneered the techniques necessary for a lunar mission.

|

|

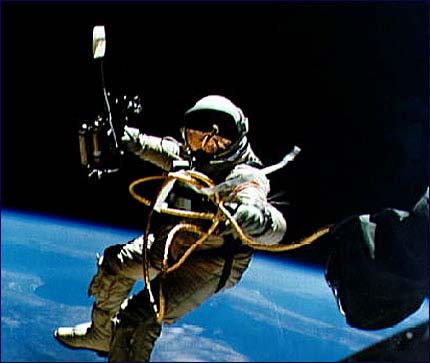

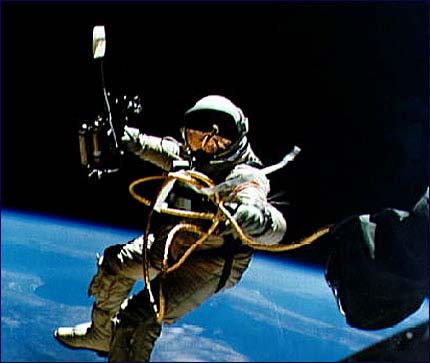

Floating outside Gemini 4, Ed White holds

a nitrogen-powered maneuvering gun.

|

They made space walks, some lasting more than two hours. They spent a

record-breaking 14 days in space -- the expected duration of a lunar landing

flight -- in a cabin no bigger than the front seat of a Volkswagen. (One

astronaut later called the two-week Gemini 7 flight "the most heroic

mission of all time.")

They mastered the arcane complexities of orbital mechanics to achieve the

first rendezvous between two spacecraft in orbit, and the first space docking.

And they made the first controlled reentries into the Earth's atmosphere.

To be sure, the Gemini missions had their harrowing moments, none more so

than when Gemini 8 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Dave Scott barely escaped

disaster when one of their maneuvering thrusters malfunctioned, causing their

spacecraft to tumble wildly through space.

And several spacewalkers had their own difficulties -- working in

weightlessness was trickier than NASA expected, and more than one sortie had to

be cut short when an astronaut became exhausted. Despite these problems, Gemini

was considered a tremendous success. It gave the United States the lead in the

space race, which was about to become a moon race.

Robotic Explorers

|

|

Mariner 4's first closeup image of Mars in 1965.

|

Meanwhile, the Americans and Soviets were extending humanity's reach beyond

Earth orbit by means of ever more sophisticated robotic probes. The U.S.

Mariner 2 became the first interplanetary spacecraft when it flew past Venus in

1962 and sent back data about this cloud-hidden world. Another American craft,

Mariner 4, took the first closeup pictures of Mars in 1965.

Closer to home, in 1966, the Soviet Union achieved the first soft landing of

a spacecraft on another world, when Luna 9 came to rest on the moon's Ocean of

Storms and sent back images of its dusty surface.

Also in 1966, U.S. Surveyor landers began exploring the lunar surface, and a

series of Lunar Orbiter spacecraft began a detailed photo-reconnaissance of the

moon from orbit. These missions not only advanced scientific understanding of

Earth's nearest neighbor; they helped pave the way for the piloted missions

that would follow.

Disaster and Triumph

By 1967, both the United States and the Soviet Union were ready to test the

spacecraft they would use to send humans to the moon. In the process, both

countries suffered devastating failures.

On January 27, 1967, the crew of the first piloted Apollo mission --

veterans Gus Grissom and Ed White, and rookie Roger Chaffee -- perished when a

flash fire swept through the sealed cabin of their Apollo 1 command module.

NASA's investigation of the tragedy revealed numerous technical flaws in the

craft's design, including the need for a quick-opening hatch, and fireproof

materials in the cabin. The fire would ultimately delay the Apollo program for

more than 20 months.

Disaster struck the Soviets in April 1967, when cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov

piloted Soyuz 1 ("union"), an Earth-orbit precursor of a planned

lunar-orbit vehicle. When Komarov's flight was plagued by malfunctions,

controllers ordered him to come home early. But the craft's parachute did not

deploy properly, and Soyuz 1 slammed into the Earth at tremendous speed,

killing Komarov. The Soviets too had found that winning the moon race could

exact a terrible price.

|

|

Apollo 4 liftoff.

|

For the Americans, at least, 1967 ended on a triumphant note with the debut

of the giant Saturn 5 moon rocket. Towering 363 feet above its launch pad, the

Saturn's three stages contained as much chemical energy as an atomic bomb.

When it lifted off on November 9, with 7.5 million pounds of thrust, the

Saturn's fire and thunder were truly awesome to behold. For NASA, the Saturn

5's flawless test flight marked a key milestone on the road to the moon.

Apollo rising

Americans returned to space on October 11, 1968, when the crew of Apollo 7

made an 11-day Earth-orbit test of the Apollo command and service modules,

which had been redesigned in the wake of the fire.

The flight went so well -- one mission controller dubbed it "101

percent successful" -- that NASA decided to take a stunningly bold step

with Apollo 8: its crew would orbit the moon.

There was a note of urgency in the plan: Intelligence reports showed that

the Soviets, who had recovered from the loss of Soyuz 1, were planning to send

two cosmonauts on a circumlunar flight before the end of the year.

But after two unpiloted circumlunar test flights experienced malfunctions in

the fall of 1968, Soviet officials refused to give the go-ahead for a piloted

mission.

|

|

Apollo 8 Earthrise.

|

The way was clear for the Apollo 8 crew -- Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and

Bill Anders, to make history.

On December 24, 1968, after a 66-hour journey across 230,000 miles of space,

the three men fired their spacecraft's main engine to go into lunar orbit. They

remained there for 20 hours, making navigation sightings, taking photographs

and beaming live television pictures back to Earth, before returning home.

After a reentry at 25,000 miles per hour -- faster than humans had ever

traveled -- Borman's crew splashed down safely in the waters of the Pacific.

Apollo 8 was more than a technical triumph, more even than a milestone in

exploration: It was a mountaintop experience for the entire human species. A

single photograph from Apollo 8, showing the Earth rising beyond the moon's

barren horizon, became one of the century's most famous and inspiring images.

For the Soviets, Apollo 8's success was a stinging defeat that seemed to

take the wind out of their own moon effort, at least temporarily. For NASA, it

had the opposite effect. Now the way was clear to attempt the lunar landing. If

all went well on Apollos 9 and 10, Apollo 11 would try for a landing the next

summer. But that was a big "if"; each mission ranked as one of the

most complex and difficult space missions ever attempted.

|

|

Apollo 9 space walk

|

Amazingly, both Apollo 9 -- an Earth-orbit test of the entire Apollo

spacecraft -- and Apollo 10 -- a "dress rehearsal" for the landing in

lunar orbit -- were almost flawless.

When Apollo 10 splashed down on May 26, Neil Armstrong and his Apollo 11

crew had less than two months left to prepare for the ultimate test flight.

To Land on the Moon

July 16, 1969 dawned clear and hot for the spectators (estimated at a

million people) who flocked to Cape Kennedy for the Apollo 11 launch.

They were not disappointed.

At 9:32 a.m., the Saturn 5 came to life, its fire akin to a second sun, its

roar shattering the morning stillness as it sent Armstrong and crewmates Buzz

Aldrin and Mike Collins on history's third lunar voyage. Three days later the

men arrived in lunar orbit, knowing that their real mission -- the landing

attempt -- was about to begin.

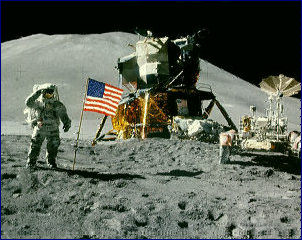

On July 20, Armstrong and Aldrin, clad in their space suits, took their

places in the tiny cabin of the Lunar Module Eagle, leaving Collins to

pilot the command ship Columbia. The two ships separated, and with a

blast from their lander's descent engine, Armstrong and Aldrin began their trip

down to the moon's Sea of Tranquillity.

At 50,000 feet they ignited Eagle's engine once more, beginning the

landing's final phase, called the Powered Descent. Everyone knew there could be

problems, and there were: On the way down, an overloaded computer threatened to

abort the mission; only quick thinking by experts in mission control allowed

Armstrong and Aldrin to continue.

A thousand feet above the moon, Armstrong saw that the craft was heading for

a crater the size of a football field that was rimmed with boulders as big as

automobiles.

Taking control, he steered Eagle to a clear spot and brought the

craft into a vertical descent, while Aldrin called out the diminishing

altitude. With his fuel supply running low, Armstrong struggled to see his

landing spot through a storm of moon dust kicked up by the descent engine.

Finally, a blue light on the instrument panel signaled that three metal

probes on Eagle's footpads had touched the moon.

"Contact light," announced Aldrin. Eagle settled gently

onto the dusty lunar ground, and Armstrong shut down the engine. The two men

turned to each other and shook hands in a brief moment of celebration.

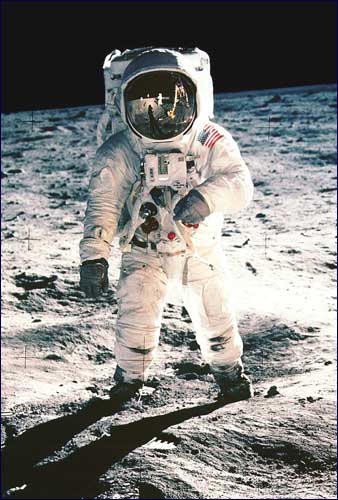

|

|

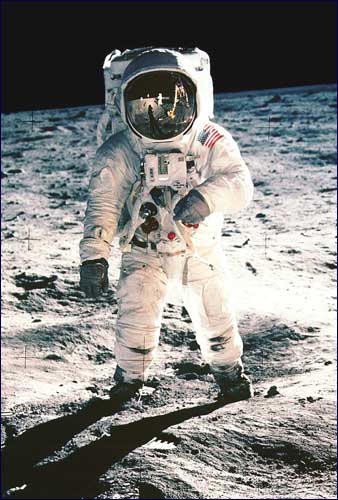

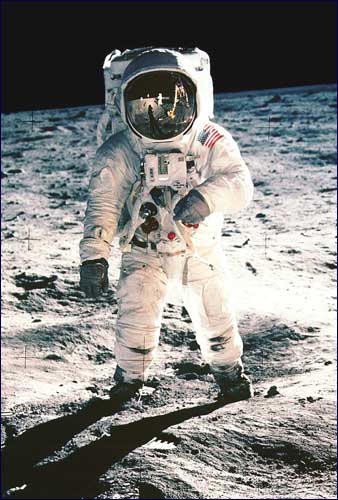

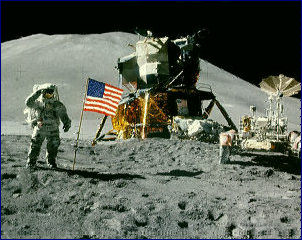

Aldrin on the moon.

|

Then Armstrong radioed to a waiting Earth, "Houston, Tranquillity Base

here. The Eagle has landed."

Almost seven hours later, Armstrong emerged from Eagle. After

descending the ladder on the craft's front landing leg, he planted his left

foot on the ancient dust of the Sea of Tranquillity, and declared: "That's

one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind."

Minutes later, Aldrin joined him on the surface, and for a bit less than two

hours, the two men collected rocks, planted the American flag, and took

pictures.

They also experienced the delights of moving in the moon's one-sixth

gravity, and marveled at the beauty of the utterly pristine, utterly ancient

lunar landscape. Then it was time for history's first moonwalk to end, as the

astronauts climbed back into their lander for a fitful rest.

On July 21, the moment of truth for Armstrong and Aldrin was at hand: the

firing of Eagle's ascent rocket to return them to lunar orbit, and a

reunion with Collins. Everyone, on Earth and in space, knew that the engine had

to work, or Armstrong and Aldrin would face a lonely death on the moon.

When the prescribed moment came, Aldrin pushed a button on the onboard

computer, and after a brief moment, the engine ignited with an invisible flame.

Amid a spray of insulation, Eagle ascended like a super-fast, silent

elevator, heading for a rendezvous with Columbia. Apollo 11's safe

return on July 24 marked the beginning of a new age, one in which human beings

could truly be called a spacefaring species.

For NASA, the age of lunar exploration was only beginning: More landings

were ahead, including Apollo 12's pinpoint lunar touchdown in November.

The United States had won the moon race. But the 1970s would bring a change

of fortunes for the space agency, while the Soviet Union blazed a new trail, as

pioneers of long-duration space missions.

Timetable of Space Events: 1960s

|

Piloted

missions |

|

Achievement |

Country |

Crew |

Spacecraft |

Launch Date |

|

First man in space |

Soviet Union |

Gagarin |

Vostok 1 |

April 12, 1961 |

|

First American in space |

United States |

Shepard |

Freedom 7 |

May 5, 1961 |

|

First day-long spaceflight |

Soviet Union |

Titov |

Vostok 2 |

August 6, 1961 |

|

First woman in space |

Soviet Union |

Tereshkova |

Vostok 6 |

June 16, 1963 |

|

First multi-person

spaceflight |

Soviet Union |

Komarov, Yegorov,

Feoktistov |

Voskhod 1 |

October 12, 1964 |

|

First space walk |

Soviet Union |

Belyayev, Leonov |

Voskhod 2 |

March 18, 1965 |

|

First 8-day space mission |

United States |

Cooper, Conrad |

Gemini 5 |

August 21, 1965 |

|

First space rendezvous |

United States |

Schirra, Stafford |

Gemini 6 |

December 15, 1965 |

|

First two-week space

mission |

United States |

Borman, Lovell |

Gemini 7 |

December 4, 1965 |

|

First space docking |

United States |

Armstrong, Scott |

Gemini 8 |

March 16, 1966 |

|

First lunar orbit flight |

United States |

Borman, Lovell, Anders |

Apollo 8 |

December 21, 1968 |

|

First lunar landing |

United States |

Armstrong, Collins, Aldrin |

Apollo 11 |

July 16, 1969 |

|

Robotic

missions |

|

Achievement |

Country |

Spacecraft |

Launch Date |

|

First closeup photos of

moon |

United States |

Ranger 7 |

July 28, 1964 |

|

First interplanetary flyby |

United States |

Mariner 2 |

August 27, 1962 |

|

First closeup photos of

Mars |

United States |

Mariner 4 |

November 28, 1964 |

|

First photos from moon's

surface |

Soviet Union |

Luna 9 |

January 31, 1966 |

|

First lunar satellite |

Soviet Union |

Luna 10 |

March 31, 1966 |

|

First automatic space

docking |

Soviet Union |

Cosmos 186-188 |

October 27 / October 30,

1967 |

http://www.space.com/spacehistory/greatest_space_events_1960s.html

Copyright ©1999 space.com, inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Greatest Space Events of the 20th Century: The Seventies

By Andrew Chaikin,

space.com Excecutive Editor, Space and Science

posted: 11:12 am EST 30 December 1999

For NASA, the sixties had ended in triumph: Humans had walked on the moon, and NASA

had put them there. For the space agency, the success of the first lunar

landing was an invitation to dream even bigger dreams. NASA administrator Tom

Paine and his deputies planned a stunning array of space activities so

extensive that they would live up to the vision presented in Collier's

magazine in the 1950s. There would be space stations in Earth orbit, a base on

the moon, and human missions to Mars.

For NASA, the sixties had ended in triumph: Humans had walked on the moon, and NASA

had put them there. For the space agency, the success of the first lunar

landing was an invitation to dream even bigger dreams. NASA administrator Tom

Paine and his deputies planned a stunning array of space activities so

extensive that they would live up to the vision presented in Collier's

magazine in the 1950s. There would be space stations in Earth orbit, a base on

the moon, and human missions to Mars.

But these dreams were met by a new, harsh reality: the 1960s

"heyday" for space budgets was over. National priorities had shifted

since John Kennedy had challenged the nation to a lunar landing by decade's

end. The country was preoccupied with an ongoing struggle for civil rights and

dissent over the war in Vietnam. The booming economy of the early 1960s had

given way to concern over inflation. Space exploration no longer headed the

Cold War agenda. And so, when the Nixon administration responded to NASA's

budget requests, Paine's grand vision fell by the wayside.

|

|

Skylab over earth

|

Only one element of the plan was preserved by the White House and Congress:

A reusable space shuttle that would ferry astronauts to and from Earth orbit.

The shuttle would launch satelllites, and serve as an orbiting research

platform. And NASA promised it would lower the high cost of access to space.

The shuttle would not be ready to fly until 1978 at the earliest. Meanwhile,

a program called Skylab would serve as a follow-on to Apollo. With Skylab, an

Earth-orbit space station constructed largely from spare Apollo hardware,

astronauts would go from visiting space to living there. With as much living

space as a small house, Skylab crews would spend up to three months operating

astronomical telescopes to study the Sun, special cameras to photograph the

Earth in selected wavelengths of light, and other experiments designed to study

the behavior of materials in weightlessness. The astronauts would also study

themselves with a slew of medical experiments.

Apollo's Scientific Finale

Meanwhile, the Apollo moon missions continued to rack up extraordinary

accomplishments. Simply getting to the moon and back had been the goal of the

first Apollo landing crew. But beginning with Apollo 12, the mission began to

emphasize scientific exploration. In November 1969 Apollo 12 astronauts Pete

Conrad and Alan Bean had made history's first pinpoint lunar landing by

touching down within walking distance of the robotic Surveyor 3 probe, which

had rested on the moon's Ocean of Storms since early 1967. In the process, they

had demonstrated that future Apollo crews could set down at some of the most

geologically enticing places on the moon.

|

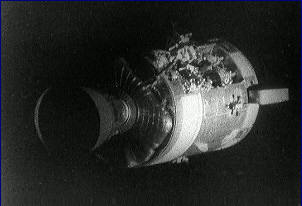

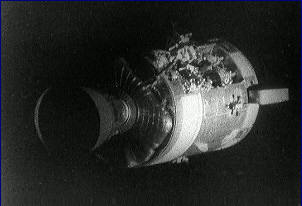

|

Apollo 13's damaged service module,

seen shortly before reentry.

|

Scientists' hopes were high for the Apollo13 mission which left Earth on

April 11, 1970, bound for the moon's Fra Mauro highlands. But those hopes

evaporated some 55 hours into the mission, when an oxygen tank exploded aboard

the Apollo 13 service module, aborting the flight and plunging NASA into the

worst crisis it had ever faced on a piloted space mission.

Aboard the crippled spacecraft, lunar veteran Jim Lovell and his rookie

crew, Jack Swigert and Fred Haise, were forced to abort their mission and begin

an emergency trip home. To survive, they used their lunar lander as a lifeboat,

utilizing its oxygen, radio, and rocket engines. By the time they reached Earth

four days later, the men were exhausted and battling bone-chilling conditions

aboard their spacecraft. But the combined efforts of the astronauts and

hundreds of flight controllers and engineers on Earth paid off: Lovell's crew

splashed down safely on April 17, crowning a recovery effort that many called

NASA's finest hour.

Picking up the torch from Jim Lovell's crew, Apollo 14 was led by America's

first space traveler, Alan Shepard, who had been grounded since his 1961

Mercury mission by an inner-ear disorder, but restored to health after an

experimental surgery. Shepard's footsteps on the Fra Mauro highlands

represented not only a success for NASA, but a personal triumph.

In the summer of 1971, Apollo's scientific phase got into high gear, as

Apollo 15's Dave Scott and Jim Irwin became the first astronauts to explore the

mountains of the moon. They brought along a new innovation: a battery powered

car called the Lunar Rover that allowed them to range for miles across the

landscape on geologic "treasure hunts."

|

|

Apollo 15's Jim Irwin poses with the

lunar module and lunar rover (right).

|

For three days, Scott and Irwin lived and worked among the moon's Apennine

mountains. Among their finds was a rock that dated back 4.5 billion years,

almost as old as the moon itself, which became known as the "Genesis

rock." Meanwhile, circling the moon, crewmate Al Worden operated a battery

of scientific cameras and sensors in an intensive orbital reconnaissance.

Even as Apollo 15 demonstrated the new heights Apollo had reached, budget

cuts were bringing the program to a premature end. In 1970 three lunar missions

were canceled, leaving only Apollo 16 and 17 to write the final chapters in the

Apollo saga.

In December 1972, Apollo 17 saw Gene Cernan and geologist-astronaut Jack

Schmitt -- the first professional scientist to visit another world -- explore

the spectacular Taurus Littrow valley, while Ron Evans surveyed the moon from

orbit. When Apollo 17 splashed down in the Pacific, the 20th

century's brief era of human exploration of the moon was over.

Lunar Robots Rock n' Roll

By the early 1970s, the Soviet Union was forced to abandon its efforts to

send people to the moon. Even before Apollo 11's lunar landing, Soviet space

planners had realized they would likely lose the moon race. They had begun

their lunar program relatively late, a few years after the Americans.

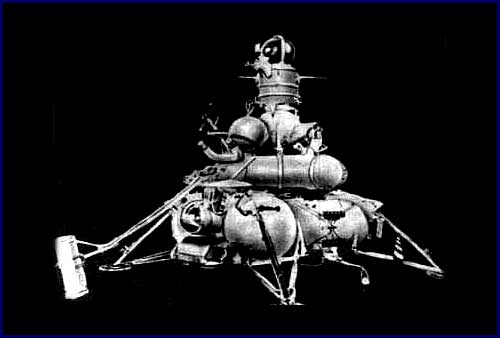

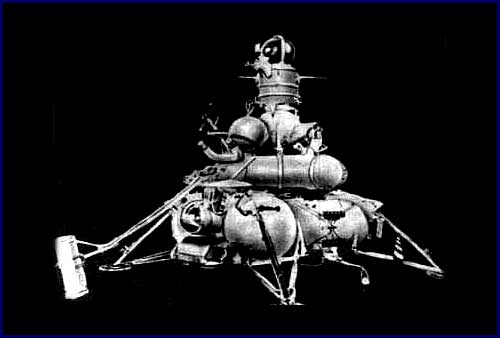

|

|

The Soviet Union

launched Luna 16 in

September, 1970. It was the first robotic

probe to land on the moon and return

a sample to Earth.

|

But the most severe blow came from the failure of Sergei Korolev's giant N-1

moon rocket: It exploded during each of its four test-launches between 1969 and

1972. Some still dreamed of catching up with the U.S. program, or even

surpassing it, by establishing a lunar base. But the repeated failures of the

N-1 put an end to such plans. Korolev wasn't around to see his dream abandoned;

he had died during surgery in 1966.

As an alternative, the Soviets staged a series of robotic missions in an

attempt to show the world that they could duplicate Apollo's scientific

harvest, for a fraction of the cost. The first tries at an automated lunar

sample-return came before Apollo 11. But success did not come until September,

1970: Luna 16 touched down on the Sea of Fertility, drilled into the soil, and

launched a return capsule to Earth bearing a small vial of lunar dust and rock

fragments. Luna 20 repeated the feat in 1972, and Luna 24 retrieved a sample

from the Sea of Crisis in 1976.

The Soviets also deployed a pair of automated rovers which roamed the moon

under remote control by engineers on Earth. Named Lunakhod, the rovers were

equipped with television cameras and scientific instruments to investigate the

properties of lunar soil. Lunakhod 1 reached the Sea of Rains in 1970; Lunakhod

2 traveled the Sea of Serenity in 1973.

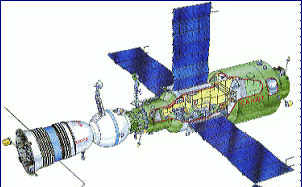

Soviet Space Marathons

Beginning in the early 1970s, the Soviets' human spaceflight program charted

a new course, into Earth orbit. In 1971, two years before NASA's initial Skylab

mission, they launched the world's first space station, Salyut 1. Three

cosmonauts spent 21 days aboard the station, but their mission ended

tragically: All three men died after a sudden loss of cabin pressure

immediately before their spacecraft made an automatic reentry. Ground teams

rushed to the craft only to find the crew dead inside.

|

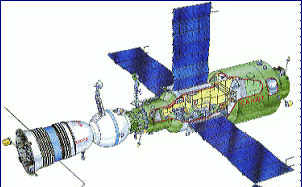

|

Cutaway view of the Salyut 4 space station,

with Soyuz ferry attached (left).

|

By September, 1973, the Soviets had recovered from the tragedy and were back

to launching Salyuts for scientific missions. They also inaugurated a series of

Almaz space stations for military reconnaissance, further evidence that the

Cold War was being waged in space as well as on Earth.

The Salyut missions put the Soviet Union at the frontier of long-duration

spaceflight. With a four-month residence on Salyut 6 in 1978, the crew of Soyuz

29 broke the U.S. space endurance record set aboard Skylab. The following year

Soyuz 32 cosmonauts Vladimir Lyakhov and Valeri Ryumin cosmonauts logged an

extraordinary stay of six months the station. Even that record would be

surpassed as the Soviet space marathons continued into the 1980s.

Other Nations in Space

International space activities blossomed in the 1970s. Beginning in 1973,

ten European nations joined forces to form the European Space Agency, or ESA.

ESA's members embarked on a variety of space projects, including development of

a new satellite launcher called Ariane. The first successful Ariane launch in

1979 ushered in a new era of commercial space activities.

Also in 1975, détente found its way into space, if only for a moment, as

the U.S. and Soviet Union staged a joint space mission called the Apollo-Soyuz

Test project. The dual mission, which commanded by Apollo veteran Tom Stafford

and Soviet spacewalker Alexei Leonov, featured the first international space

docking.

The 1970s also saw a growing number of nations launching satellites. China's

first, lofted in 1971, broadcast a melody entitled "East Is Red."

India, whose first satellite was launched by the Soviets in 1975, achieved its

own satellite launch in 1979.

Planetary Exploration's Golden Age

|

|

The Viking 1 lander

reached Mars in 1976.

|

In the 1970s, planetary exploration flourished as U.S. and Soviet robotic

missions sent back a phenomenal haul of data. Mars was the target of the

Mariner 9 spacecraft, which began mapping the planet from orbit in 1971.

Mariner's images revealed towering volcanoes, giant canyons, and winding

valleys that appeared to be dry river beds. In 1976, the twin Viking landers

made the first successful touchdowns on the martian surface, sending back

images and data on the planet's atmosphere and soil. The Vikings' most

celebrated experiment -- a search for signs of microbial life -- failed to find

any conclusive evidence.

|

Rocks on the surface of Venus,

photographed by Venera 9 in 1975.

|

|

The Mariner 10 spacecraft was the first to take advantage of a technique

called gravity assist: During a flyby of Venus, the probe used the planet's

gravity to redirect it toward Mercury. Thanks to a lucky coincidence between

Mercury's orbital period and the spacecraft's trajectory, Mariner 10 made not

one but three flybys of the innermost planet.

|

|

This view of Jupiter

was taken by Voyager 1

|

The Soviets, who had little success in several Mars landing attempts,

succeeded with an even more challenging task: Their Venera landers actually

survived a descent to the hellish surface of Venus. Beneath the planet's dense,

opaque atmosphere, the Venera's found surface pressures 90 times that on Earth,

and temperatures as high as 900 degrees Fahrenheit -- hot enough to melt lead.

The Venera landings gave scientists their first images and in situ data

on the planet's surface composition. But in the 1970s, Venus was the only truly

successful target for Soviet planetary missions.

The United States, meanwhile, turned its attention to the outer solar system

with the Pioneer 10 and 11 spacecraft. These twin probes made the first flybys

of Jupiter and Saturn, sending back valuable glimpses of these planets' cloudy

atmospheres, and valuable data on their powerful magnetic fields. The more

sophisticated Voyager 1 and 2 probes, launched in 1977, began their own

"grand tour" of the outer solar system, a mission that would

ultimately stretch to the end of the 1980s, and even beyond.

Apollo image gallery

NASA-JSC Digital Image Collection

NASA History Office

Russian Space History

Timetable of Space Events: 1970s

|

Piloted

missions

|

| Achievement |

Country |

Crew |

Spacecraft |

Launch

Date |

|

First space

station |

Soviet Union |

Dobrovolski,

Volkov,

Patsayev |

Soyuz 11,

Salyut 1 |

June 6, 1971 |

|

First visit to

lunar mountains; first lunar rover |

United States |

Scott, Worden,

Irwin |

Apollo 15 |

July 26, 1971 |

|

First

one-month mission |

United States |

Conrad, Kerwin,

Weitz |

Skylab 2 |

May 25, 1973 |

|

First

two-month mission |

United States |

Bean, Garriott,

Lousma |

Skylab 3 |

July 28, 1973 |

|

First

three-month mission |

United States |

Carr, Gibson,

Pogue |

Skylab 4 |

November 16,

1973 |

|

First military

space station |

Soviet Union |

(several

crews) |

Salyut 2 |

June 24, 1974 |

|

First

international piloted space mission |

United States,

Soviet Union |

Stafford,

Brand, Slatyton (US);

Leonov, Kubasov (USSR) |

Apollo-Soyuz |

July 15, 1975 |

|

First

four-month mission |

Soviet Union |

Kovalyonok,

Ivanchenkov |

Soyuz 29,

Salyut 6 |

June 5, 1978 |

|

First

six-month mission |

Soviet Union |

Lyakhov,

Ryumin |

Soyuz 32,

Salyut 6 |

February 25,

1979

|

|

Robotic

missions

|

| Achievement |

Country |

Spacecraft |

Launch

Date |

|

First automated lunar sample

return |

Soviet Union |

Luna 16 |

September 12, 1970 |

|

First automated lunar rover |

Soviet Union |

Lunakhod 1 |

November 10, 1970 |

|

First Mars orbiter |

United States |

Mariner 9 |

May 9, 1971 |

|

First Jupiter flyby |

United States |

Pioneer 10 |

March 3, 1972 |

|

First Saturn flyby |

United States |

Pioneer 11 |

April 6, 1973 |

|

First Mercury flyby |

United States |

Mariner 10 |

November 3, 1973 |

|

First Venus landing |

Soviet Union |

Venera 9 |

June 8, 1975 |

|

First Mars landing |

United States |

Viking 1 |

August 30, 1975 |

|

First detailed

reconnaissance

of Jupiter and its moons |

United States |

Voyager 1 |

September 5, 1977

|

http://www.space.com/spacehistory/greatest_70s_991230.html

Copyright ©1999 space.com, inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Greatest Space Events of the 20th Century: The 80s

By Andrew Chaikin,

space.com Executive Editor, Space and Science

posted: 06:44 am EST 03 January 2000

|

|

STS-1, the first

shuttle launch

|

On April 12, 1981, twenty years to the day after Yuri Gagarin became the

world's first space traveler, a new type of space vehicle stood ready for

launch at the Kennedy Space Center. To the eye it appeared as an unlikely

collection of forms: Something resembling an airplane, standing on its tail,

was attached to a huge cylinder the size of a grain silo, which in turn was

accompanied by a pair of slender rockets.

This was the Space Shuttle Columbia, first of a planned fleet of

reusable spaceships. The winged shuttle orbiter, the size of a commercial

jetliner, was designed for a hundred trips into space. Drawing its fuel from a

giant external tank, the orbiter's three engines would deliver 4.3 million

pounds of thrust at liftoff, with an additional 2.6 million pounds of thrust

being supplied by twin solid rocket boosters.

With a 60-foot-long cargo bay, the shuttle was capable of carrying new

satellites into space, or retrieving an ailing spacecraft for repair. NASA

hoped the shuttle would usher in a new era of spaceflight. So did the new corps

of astronauts selected to fly it; for the first time in the U.S. space program

they included women and minorities.

Columbia's commander was John Young, veteran of Gemini and Apollo, and

one of the world's most experienced space travelers. Together with his

co-pilot, a rookie named Bob Crippen, Young had prepared for more than two

years to fly the shuttle's maiden voyage, officially designated STS-1

("STS" stands for Space Transportation System).

Everyone knew the risks Young and Crippen were taking: The shuttle was the

most complex space vehicle ever devised, and there were countless possibilities

for things to go wrong, bringing failure or even disaster.

The Shuttle Era Begins

|

|

Astronaut Bruce McCandless,

mission

specialist, a few meters away from the

cabin of the shuttle Challenger.

|

When the moment of launch came, however, everything worked perfectly.

Seconds before liftoff Columbia's three main engines ignited, followed

by the two solid rocket boosters, and the shuttle roared toward orbit. In

space, the astronauts discovered that the orbiter had lost some of its

heat-protective silica tiles, raising concerns for the craft's fiery reentry

into the Earth's atmosphere.

But Columbia performed, in Young's words, "like a champ,"

and the mission ended on April 14 with a picture-perfect landing on a desert

runway at California's Edwards Air Force Base. Addressing a crowd of

well-wishers Young declared, "We're really not too far, the human race

isn't, from going to the stars."

Later in 1981,Columbia proved its reusability by flying a second

mission, and in 1982 it flew three more. The orbiter's fifth flight, STS-5, was

also the first operational mission of the shuttle program, and inaugurated the

shuttle as a satellite launcher, leaving two commercial communications

satellites in Earth orbit.

STS-5 also featured the first so-called mission specialists, astronauts

whose job was not to fly the orbiter but to carry out experiments and other

tasks in orbit. Up to six mission specialists -- for a total crew of eight

people -- could fly on the shuttle at once.

In February 1984, spacewalking shuttle astronauts tested a Buck Rogers-style

jet-pack called the Manned Maneuvering Unit. In April of that year,

spacewalkers Pinky Nelson and Ox van Hoften became the first on-site satellite

repairers when they fixed the ailing Solar Maximum Mission astronomical

satellite.

Disaster Strikes

|

|

STS-51L Mission Control:

"Obviously . . . a major malfunction."

|

By late 1985, NASA was operating a fleet of four shuttle orbiters and

setting a record pace of launches. That year nine shuttle missions were flown,

and even more flights were planned in 1986. There was even a program in the

works to fly ordinary citizens in space.

There was reason for the break-neck pace. The shuttle had not lowered the

costs of access to Earth orbit. And for commercial launches, NASA was facing

stiff competition from Europe's Ariane rocket, which enjoyed government

subsidies and lower operating costs. NASA's original forecasts had called for a

shuttle flight almost every week, and while no one at the agency believed that

goal was attainable, some still talked of flying 24 missions per year. But that

was not to be.

On January 28, 1986, the shuttle Challenger exploded 73 seconds after

liftoff, killing its seven-member crew, including schoolteacher Christa

McAuliffe. The disaster stunned the nation and shattered any illusions that

spaceflight had become routine. For NASA, it brought the realization that the

agency had been living too close to the edge.

Months of investigation by a presidential commission traced the Challenger

accident to a bad seal in a solid rocket booster. And there was also

criticism of the decision-making process that had cleared the shuttle for

launch in unusually cold conditions. As NASA struggled to recover from the

disaster, the United States scrambled to shift its satellite-launching tasks to

expendable rockets. Many payloads slated for shuttle launches, including the

Hubble Space Telescope, would face years of delay.

|

|

Mir

|

Space Station Mir

For the Soviet Union, 1986 was the beginning of a new era in long-duration

space missions, with the launching of the first modular space station, called

Mir ("Peace"). Mir, whose crews would make even longer stays, offered

somewhat more room and more "creature comforts" than Salyut. It was

also the first space station meant for continuous occupation.

Already, cosmonauts had set a new space endurance record of 237 days --

almost 8 months -- aboard the Salyut 7 space station. In December 1987,

Vladimir Titov and Musa Maranov arrived at Mir; they returned to Earth a year

later.

Around this time, the Soviets were talking openly of plans to send humans to

Mars. Before that could happen, however, long-duration missions in Earth orbit

would have to find ways of keeping space travelers healthy -- physically and

psychologically -- during months or even years in space.

To break the monotony of their space marathons, Salyut and Mir crews were

visited occasionally by teams of cosmonauts, including a number of "guest

cosmonauts" selected from various Soviet-bloc nations. They also received

shipments of mail, supplies, and gifts via unpiloted Progress spacecraft.

|

|

Buran transporter and launch

|

On Earth, meanwhile, Soviet space planners, who had feared the U.S. Space

Shuttle might be used to drop nuclear weapons, were ready to inaugurate a

shuttle of their own. Called Buran ("snowstorm"), it closely

resembled the American shuttle orbiter, but had the ability to fly under remote

control from Earth, and to make powered landings.

Buran was mated to a giant new booster called Energia for launch. But

the high costs of military and civilian space programs were catching up with

the Soviets, and Buran made only a single, unpiloted mission, in

November 1988. The following year marked the dissolution of the Soviet Union,

and the end of the Cold War that had spawned so many space accomplishments.

A Time of Limits

Funding was also an issue for the U.S. space program, especially in the area

of space science. With most of NASA's budget going to support the Space Shuttle

program, relatively little was left for robotic missions.

Although the twin Voyager probes continued to provide stunning data -- after

surveying Jupiter they flew past Saturn, and Voyager 2 continued to Uranus and

Neptune -- few successors were in the works. When Halley's Comet made a rare

appearance in the inner solar system in 1985-86, the U.S. was not among the

nations who launched space probes for close encounters with the comet.

|

|

NASA stores recovered

wreckage from the

Challenger explosion in underground silos

at Cape Canaveral previously used to house

Minutemen missiles.

|

And in the aftermath of the Challenger accident, delays and

cancellations meant that only two new planetary missions were launched during

the 1980s: the radar-equipped Magellan Venus orbiter and the Galileo Jupiter

orbiter, each dispatched by shuttle astronauts in 1989.

At the same time, NASA was working toward another of its cherished goals, a

permanent space station in Earth orbit. By the time the Space Shuttle was

flying again in September 1988, the agency had gained approval for the project.

The station became an international venture as NASA joined forces with the

European Space Agency, Canada, and Japan. At the close of the decade, however,

the station was mired in bureaucracy, its design and completion date uncertain.

The space station would continue to draw much of NASA's energies in the

1990s, as the agency struggled to redefine itself and its goals in space.

NASA Human Spaceflight

Mir space station -- Maximov online

Russianspace.com

Presidential Commission Report on Challenger Accident

Timetable of Space Events: 1980s

|

Piloted

missions |

|

Achievement |

Country |

Crew |

Spacecraft |

Launch Date |

|

First reusable spacecraft |

United States |

Young, Crippen |

Columbia |

April 12, 1981 |

|

First untethered spacewalk |

United States |

Brand, Gibson, McCandless,

McNair, Stewart |

Challenger |

February 3, 1984 |

|

First in-space satellite

repair |

United States |

Crippen, Scobee, Hart,

Nelson, van Hoften |

Challenger |

April 6, 1984 |

|

First modular space station |

Soviet Union |

(several crews) |

Mir |

February 19, 1986 |

|

First year-long spaceflight |

Soviet Union |

Titov, Maranov |

Mir space station |

December 21, 1987 |

|

Robotic

missions |

|

Achievement |

Country |

Spacecraft |

Launch Date |

|

First detailed

reconnaissnace of Saturn and its moons |

United States |

Voyager 1 |

September 5, 1977 |

|

First Uranus flyby |

United States |

Voyager 2 |

August 20, 1977 |

|

First images of cometary

nucleus (Halley) |

Soviet Union |

Vega 1 |

December 15, 1984 |

|

First Neptune flyby |

United States |

Voyager 2 |

August 20, 1977 |

http://www.space.com/spacehistory/yir_greatest1980s_000103.html

Copyright ©1999 space.com, inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Greatest Space Events of the 20th Century: The Nineties

By Andrew Chaikin and

Anatoly Zak, space.com

posted: 01:55 pm EST 05 January 2000

The 1990s began with a profound change in the world's political structure. In 1991

the Soviet Union was dissolved. The event marked the end of the Cold War that

had spawned so many space accomplishments.

The 1990s began with a profound change in the world's political structure. In 1991

the Soviet Union was dissolved. The event marked the end of the Cold War that

had spawned so many space accomplishments.

In Russia, which inherited most of the Soviet space industry, economic

hardship loomed. Russian officials found themselves having to negotiate with

Kazakhstan for access to Baikonour, their space program's main launch complex.

And the Energia-Buran program, the Russian equivalent of the U.S. space

shuttle, was officially scrapped in 1993.

Mir: crises and kudos

The upheavals, however, did not prevent Russia from making the 1990s an

extraordinary decade in human spaceflight.

The Mir space station, launched in 1986, continued to host crews for

ever-longer missions. In March 1995 physician-cosmonaut Valeri Polyakov

concluded an astonishing 14 months aboard the station, setting a world space

endurance record that still stands.

|

|

The Space Shuttle Atlantis docked

to the Mir space station in 1995

|

That year also saw the first visits of American astronauts to Mir, something

that would have been unthinkable a decade earlier.

The Shuttle-Mir missions were designed to pave the way for future joint

space operations by the two nations. In the meantime, they gave U.S. astronauts

their first experience with long space missions since the Skylab marathons of

the early 1970s. Astronaut Shannon Lucid set a U.S. space endurance record of

six months with her Mir visit in 1996.

To NASA's surprise, some of the biggest problems that surfaced during the

Shuttle-Mir flights were cultural, not technological. The effort to merge the

space programs of two very different societies was fraught with personality

conflicts -- both in space and on the ground. There were times when NASA

engineers and astronauts working at the Moscow control center must have felt

like aliens on a hostile planet.

But their difficulties paled before the crises that assailed the Shuttle-Mir

crews. In February 1997, a serious fire blazed in one of the station's modules

when an oxygen generator malfunctioned, nearly forcing U.S. astronaut Jerry

Linenger and his Russian crewmates to evacuate. The fire wasn’t the end of

their difficulties; the station's plumbing leaked toxic coolant, and the two

Mir cosmonauts were besieged by a relentless workload.

Linenger's replacement, astronaut Mike Foale, had his own crisis when an

automated Progress supply spacecraft struck the station. The collision

punctured one of the station's six modules, causing an air leak that was

stopped by the quick action of the crew who sealed off the damaged compartment.

The crash also damaged one of Mir's solar panels, shutting off much of its

electrical power system. The station drifted, starved for power, until Foale

and the cosmonauts could bring the station back to life.

The collision was the worst in a seemingly endless series of equipment

failures and other problems. In the American public and media, there was

criticism and even ridicule of the Russian space station. But some experienced

observers had a different view: the station had lasted far longer than any of

its designers had a right to expect. The Mir crews had demonstrated

extraordinary courage and persistence in keeping the station alive.

By the time Mir was abandoned in the summer of 1999 -- after more than 13

years of operations -- the Russians had shown that humans could face daunting,

even terrifying problems in space, and succeed.

NASA's rocky road

|

|

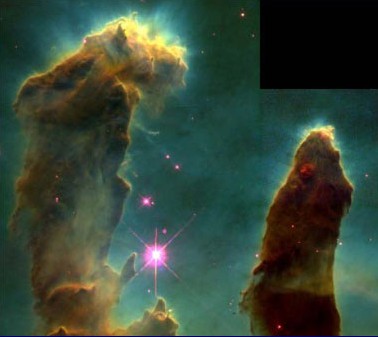

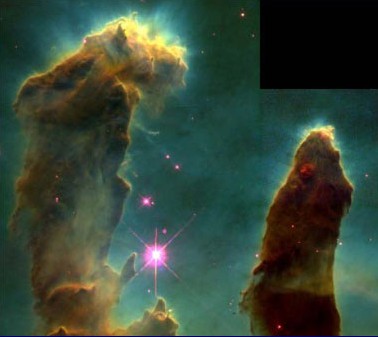

Pillars of gas and dust tower within the Eagle nebula

in this 1995 image from the Hubble Space Telescope.

|

For NASA, the 1990s got off to a shaky start. In 1990, the long-delayed

Hubble Space Telescope was deployed from Space Shuttle Discovery. But soon

after the $1.5-billion telescope reached orbit, astronomers realized its main

mirror was flawed. Already, its stunning images were delighting astronomers.

But without a difficult repair by shuttle astronauts, the telescope would never

realize its full potential.

NASA's can-do image was bolstered once more in 1993, when spacewalking

shuttle astronauts staged one of the most demanding space repair jobs ever, to

fix the Hubble Space Telescope. After receiving a set of corrective lenses, the

telescope performed even better than originally planned. The repair came just

in time for Hubble to record the crash of Comet Shoemaker-Levy into Jupiter in

July 1994.

Then, in 1992, came a mishap that transformed NASA's planetary exploration

program. That summer, scientists eagerly awaited the arrival at Mars of the

Mars Observer spacecraft, which was slated to carry out a detailed study of the

planet's surface and atmosphere from orbit. But ground stations lost contact

with the probe shortly before it was due to go into martian orbit. Analysts

concluded that the $1-billion craft was lost, probably because of a massive

fuel leak.

For NASA administrator Dan Goldin, the loss of Mars Observer hit hard. It

was clear to Goldin that the agency's long-standing penchant for big, expensive

space missions, with decade-plus lead times, had to change. When it came to

planetary exploration, NASA couldn't afford to put its eggs in a

one-billion-dollar basket. Goldin gave the agency a new motto: Faster, better,

cheaper.

|

|

Spacewalking astronauts assemble the first two modules

of the International Space Station in 1998.

|

In 1993, NASA's space station program was revamped. Already plagued by

endless delays, revisions and cost overruns, the International Space Station --

for both economic and political reasons -- would now include Russia (and

Russian space hardware from a planned Mir 2 program) as a key partner.

On the planetary exploration front, Mars was the first target for the less

expensive missions, with the Mars Surveyor program. For each new martian launch

opportunity, 26 months apart, NASA would launch a new pair of Mars spacecraft.

Another program, called Mars Pathfinder, would develop a network of small

spacecraft to land on the Red Planet. And the New Millennium program would test

new technologies for a variety of deep-space missions.

But it was a tiny spacecraft called Clementine -- a creation not by NASA,

but derived from the ill-fated "Star Wars" ballistic missile defense

program -- that first demonstrated the potential of the "faster, better,

cheaper" approach.

Clementine's arrival in lunar orbit in 1994 was the first U.S. mission to

the moon since the end of the Apollo program. While its scientific

accomplishments didn't rival Apollo's, Clementine did send back high-resolution

images and valuable data on the surface composition. And it discovered the

first signs of water on our natural satellite, in the form of ice grains

probably deposited over billions of years by comet impacts.

Mars beckons

|

|

The Sojourner rover examines a Martian boulder nicknamed Yogi in 1997

|

For Russia, Mars had long been an unrealized goal. Adding to a long string

of unsuccessful missions to the Red Planet, a pair of orbiters called Phobos 1

and 2 were lost before completing their missions in 1988.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russian space scientists faced a

new set of obstacles, namely the country's disintegrating space industry and

dwindling government funds. They worked for months without pay to prepare a new

pair of Mars spacecraft -- an orbiter and several landers outfitted with a

suite of scientific instruments -- for a November 1996 launch. The blaze of a

Proton rocket heralded the Mars '96 probe's departure. But a malfunctioning

upper stage failed to send the craft out of Earth orbit, ending the Russian's

last attempt at planetary exploration in the 1990s.

NASA scored a success in its Mars exploration program when the Pathfinder

spacecraft arrived on the Martian surface in July 1997, some 21 years after the

twin Viking probes touched down. Unlike the Vikings, however, Pathfinder used

airbags to cushion its impact. Shortly after landing, the craft deployed a

diminutive rover called Sojourner, which roamed the landing site under remote

control from Earth, examining rocks and patches of soil.

The success of Pathfinder and Sojourner, which were produced for a fraction

of Viking's cost, seemed to vindicate NASA's faster, better, cheaper credo. But

the failure of four Mars spacecraft in 1999 -- Mars Climate Orbiter, Mars Polar

Lander and a pair of Mars Microprobes -- forced the agency to reexamine the

risks of its new approach.

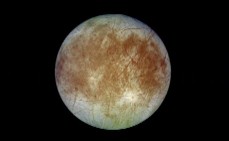

|

|

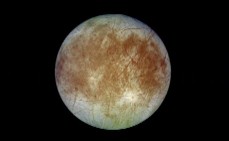

Trailing hemisphere of Europa, and

color-

enhanced close-up showing bluish water

ice and brownish double ridges.

|

Still, everyone at NASA understood that there was no turning back: the era

of high-cost planetary missions was long over. And in the aftermath of the

Polar Lander's failure in December, 1999, NASA planners focused on how to

improve chances for success in future Mars missions, including a sample-return

slated for launch in 2005.

Life beyond Earth?

The goal of returning a piece of Mars to Earth became even more alluring in

1996, when NASA scientists announced they had found evidence of fossil bacteria

inside a meteorite from Mars. While their claims remain controversial, they

moved the subject of extraterrestrial life from the fringe to the mainstream of

space science. It was clear that future Mars exploration could gather clues to

whether life exists, or ever existed, on the Red Planet.

Still farther from home, Jupiter's moon Europa yielded clues that it might

be an abode for life. High-resolution images from the orbiting Galileo

spacecraft supported theories that beneath Europa's icy crust might exist an

ocean of liquid water. It wasn't long before scientists began thinking about

21st-century robotic missions to drill through the ice and search for signs of

living organisms.

A new century in space

|

|

The unmanned Shenzhou capsule landed after 21

hours (14 orbits) in space. It is believed to

accommodate up to four "taikonauts".

|

As the 1990s ended China launched a prototype of a piloted spacecraft, with

plans to send people into Earth orbit in the first years of the new century.

The United States and Russia collaborated on a mobile, ocean-based satellite

launcher called Sea Launch. Also, NASA's Cassini orbiter, the last of the

high-cost planetary probes, was en route to Saturn.

A probe called Stardust was heading for a rendezvous with a comet, with the

goal of collecting samples of its dust for return to Earth. Crews of shuttle

astronauts deployed an orbiting X-ray telescope called Chandra, and restored

the ailing Hubble telescope to its work helping to reveal the mysteries of the

universe. The first two modules of the International Space Station circled 200

miles above the Earth, awaiting further construction. And 77-year-old John

Glenn, America's first man in orbit, became the world's oldest space traveler

when he logged a nine-day shuttle flight.

These were just a part of the universe of space activities at the end of the

20th century. And a host of space projects, in production or on the drawing

board, offered evidence that in the 21st century, human beings and their

robotic surrogates would continue to explore the final frontier.

Timetable of space events: 1990s

|

Piloted

missions |

|

Achievement |

Country |

Crew |

Spacecraft |

Launch Date |

|

World spaceflight endurance

record |

Russia |

Polyakov |

Mir |

January 8, 1994 |

|

U.S. spaceflight endurance

record |

United States |

Lucid |

Atlantis / Mir |

March 22, 1996 |

|

First docking of Space

Shuttle and Mir space station |

United States |

Gibson, Precourt, Baker,

Harbaugh, Dunbar, Solovyev, Budarin |

Discovery |

June 27, 1995 |

|

First International Space

Station visit |

United States / Russia |

Cabana, Sturckow, Currie,

Newman, Ross, Krikalev |

Endeavour |

December 4, 1998 |

|

Robotic

missions |

|

Achievement |

Country |

Spacecraft |

Launch Date |

|

First large space telescope |

United States |

Hubble Space Telescope |

April 24, 1990 |

|

First asteroid flyby |

United States |

Galileo |

October 18, 1989 |

|

First Jupiter orbiter |

United States |

Galileo orbiter |

October 18, 1989 |

|

First probe into Jupiter

atmosphere |

United States |

Galileo probe |

October 18, 1989 |

|

First planetary rover |

United States |

Pathfinder/ Sojourner |

December 4, 1996 |

|

First mobile, ocean-based

satellite launcher |

United States / Russia |

Zenit / Sea Launch |

March 28, 1999 |

http://www.space.com/spacehistory/greatest_1990s_000105.html

Copyright ©2000 space.com, inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

When you think of the 1950s, you might recall the decade's contributions to popular

culture: Rock n' Roll, hula hoops, and horror films featuring a menagerie of giant

radioactive beasts. Long after Godzilla is forgotten, however, the fifties will be

remembered as the dawn of the space age.

When you think of the 1950s, you might recall the decade's contributions to popular

culture: Rock n' Roll, hula hoops, and horror films featuring a menagerie of giant

radioactive beasts. Long after Godzilla is forgotten, however, the fifties will be

remembered as the dawn of the space age.

For NASA, the sixties had ended in triumph: Humans had walked on the moon, and NASA

had put them there. For the space agency, the success of the first lunar

landing was an invitation to dream even bigger dreams. NASA administrator Tom

Paine and his deputies planned a stunning array of space activities so

extensive that they would live up to the vision presented in Collier's

magazine in the 1950s. There would be space stations in Earth orbit, a base on

the moon, and human missions to Mars.

For NASA, the sixties had ended in triumph: Humans had walked on the moon, and NASA

had put them there. For the space agency, the success of the first lunar

landing was an invitation to dream even bigger dreams. NASA administrator Tom

Paine and his deputies planned a stunning array of space activities so

extensive that they would live up to the vision presented in Collier's

magazine in the 1950s. There would be space stations in Earth orbit, a base on

the moon, and human missions to Mars.

The 1990s began with a profound change in the world's political structure. In 1991

the Soviet Union was dissolved. The event marked the end of the Cold War that

had spawned so many space accomplishments.

The 1990s began with a profound change in the world's political structure. In 1991

the Soviet Union was dissolved. The event marked the end of the Cold War that

had spawned so many space accomplishments.