![]() Thelma and Louise - and JAK

Thelma and Louise - and JAK

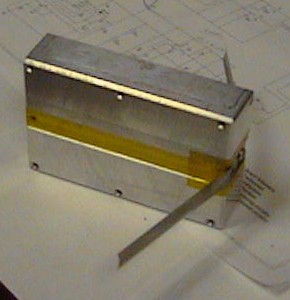

Undergrad team built puck-sized satellites using off-the-shelf parts Some of the world's smallest satellites, built by engineering students, were released into orbit last week. Senior Santa Clara University engineering students raised the money themselves — about $5,000 for each satellite — and built the tiny devices with off-the-shelf components. “They used the kind of stuff you can buy at Radio Shack,” says Christopher Kitts, the team’s adviser. For example, the half wave dipole antenna is an untreated Stanley Tools tape measure, which was wrapped around the outside of the satellite and released from its loaded position after launch. The three satellites weigh a total of 611 grams and consume only 24 cubic inches of space. When the students first got together, they had no plans to limit their membership to women. But they had a combination of mechanical and electrical engineers and a computer science major who all knew one another, so they decided to link up. They named their team Artemis, after the Greek goddess of the moon. Sandwiching the demands of the project between classes, studying, part-time jobs and the desire for some downtime was never simple. "It started out as fun, but it came to a point when we got tired," said Theresa Kuhlman, a mechanical engineer. "A lot of things didn't work the way we thought they would, so we had to change things and sometimes do them over. We were all tired of it and it was a struggle, but we knew it was something that we had to deliver within a set time frame." "Combined, I believe we spent around 5,380 hours in total, though that doesn't include a lot of the early work we did planning and meeting to talk about our progress and next steps," said Corina Hu, another EE. "Lots of the time, we spent 40 hours a week on the project. That fluctuated sometimes, like when we had finals, but I think we spent at least 20 hours per week per person on the project." The lengthy effort was even something of a motivator for some of the team members, crystallizing career plans for a couple of Artemis engineers. One is now doing graduate work at an aerospace school in France. Another has started working for Lockheed. A third is focusing on communications and seriously considering zeroing in on satellite communications. The remaining students are doing graduate work now. |

| Artemis Log | |

| January 26 7:03pm PST |

OPAL was successfully launched at out of Vandenberg Air Force Base, CA! |

| January 27 4:40am PST |

OPAL was successfully

deployed from JAWSAT and the first OPAL beacon was heard at the SSDL

ground station at Stanford University. For more up-to-date information on OPAL's status, please see here. The latest OPAL keplerian elements can be found here OPAL pass schedule calculated from the above keps can be found here. |

| February 8 | OPAL is in nominal

operations mode. OPAL has successfully ejected the first picosatellites (built by Aerospace Corp.) into orbit Multiple confirmations: NORAD tracking, pico beacon, and OPAL onboard telemetry |

| February 10 | JAK was commanded to

launch from OPAL during the 7pm PST pass over Stanford tonight Still waiting for confirmation ... Keps will be published as soon as they're available Thelma and Louise are soon to follow Congratulations to Aerospace for successfully completing their picosatellite operations |

| February 11 | T & L are scheduled

to be released from OPAL during the 2/12 5:40am PST pass over

Stanford Tracked objects around OPAL has confirmed JAK and StenSat ejection from OPAL. During the morning pass, downloaded OPAL telemetry confirmed JAK's ejection No signal has been heard from JAK ... Stay Tuned... |

| Space Command has confirmed pico launch and is tracking them. We hope to have 2 line elements soon. Unfortunately, no one has heard from JAK and only a faint transmission for STENSAT. JAK's battery is assumed dead by now. | |

| February 12 05:43:53 PST |

Thelma and Louise (a.k.a.

Thunder and Lightning) were launched from OPAL. No signal has been heard from T & L ... Our fingers are crossed ... Congratulations to OPAL for successfully completing ALL of the short-term mission |

| February 15 | Here are the first set of

keplerian elements released for T & L: 1 26091U 00004J 00045.45063363 .00001219 00000-0 45366-3 0 60 2 26091 100.2238 245.3493 0036795 138.0359 222.3612 14.34054168 212 1 26092U 00004K 00045.45011358 -.00000032 00000-0 94394-5 0 57 2 26092 100.2147 245.3481 0038555 140.1252 220.2732 14.34446112 237 |

The Picosats

|

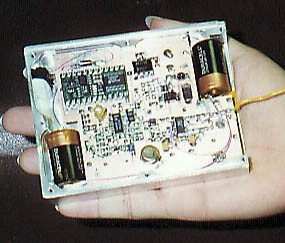

Thelma and Louise (aka

Thunder and Lightning) use a 68HC11 processor with memory, gallium-arsenide solar cells and AA batteries, as well as sensors.

Thelma and Louise (aka

Thunder and Lightning) use a 68HC11 processor with memory, gallium-arsenide solar cells and AA batteries, as well as sensors.

Very low-frequency transmitters and receivers communicate with both the mother satellite and earth stations over amateur radio frequencies. After they’re launched by the mother ship, the two slowly drift apart.

Each carries a receiver to record radio waves in the ionosphere caused by lightning. The ionosphere is a poorly understood region in Earth’s upper atmosphere, and electromagnetic disturbances there can wreak havoc on communication satellites. The tiny satellites receive the same blast coming from the same stroke of lightning, and transmit that data back to the ground. Since they’re separated, any differences in the signals will tell scientists something about the part of the ionosphere that the radio waves passed through.

Rubber ferrite magnets help

control the spin axis, aligning it relative to the Earth's magnetic field,

to enhance the data accumulation for the VLF experiment.

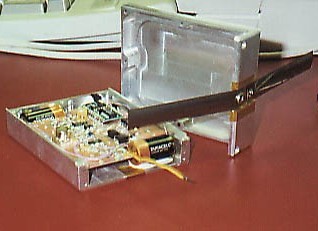

JAK, A third, less complex module simply broadcasts the Artemis Web site in Morse code. Ham radio operators who hear the code and check the site will realize they've been communicating with an orbiting satellite.

JAK, A third, less complex module simply broadcasts the Artemis Web site in Morse code. Ham radio operators who hear the code and check the site will realize they've been communicating with an orbiting satellite.

Students Make Mini Satellites

Students Make Mini Satellites

An all-female undergrad team has earned the chance to build puck-sized satellites using off-the-shelf parts

|

The Artemis team, from left to right: Adelia Valdez, Theresa Kuhlman, Amy Slaughterbeck, Dina Hadi, Shannon Lyons and Corina Hu. Seated is Maureen Breiling. (Stanford University) |

Seven students at Santa Clara University in Northern California prove that you don’t have to be rich, have a corporate sponsor, or even be male to launch satellites into orbit.

Making it into space these days just requires a good idea, backed up by lots of hard work.

The all-female team — virtually unheard of in the male-dominated space business — is putting the finishing touches on three tiny satellites scheduled to launch in September.

Members of the team are senior engineering students who raised the money themselves — about $5,000 for each satellite — and built the tiny devices with off-the-shelf components.

“They used the kind of stuff you can buy at Radio Shack,” says Christopher Kitts, the team’s adviser and co-director of the Santa Clara Remote Extreme Environment Mechanisms Laboratory.

One of the satellites built by the team that calls itself Artemis, after the Greek goddess of the moon, wild animals and hunting. (Santa Clara University) |

The hockey puck-sized satellites are designed to carry out scientific research, he says.

The satellites will piggyback aboard a Stanford University-built 30-pound satellite called OPAL. The Orbiting Picosatellite Automated Launcher will serve as a mother ship, spitting out smaller devices provided by such giants as the Department of Defense and the Aerospace Corp. — as well as Santa Clara’s hockey pucks.The mission will see if small satellites equipped with tiny sensors can survive the rigors of space and do the work of much larger and more expensive vehicles.

Seniors Stepping Up

Research universities and graduate students routinely participate in space projects, but it’s unusual for undergraduates to have a lead role.

The Santa Clara project began about a year ago, when students expressed an interest in building some sort of spacecraft.

Kitts, who was finishing his work toward a doctorate in mechanical engineering with a specialty in satellite design at Stanford, was intrigued.

He told the Santa Clara students to form teams and develop their ideas as team projects. One team ended up composed of all women, and they eventually won the competition. Kitts says it isn’t because it was an all-female effort.

“We picked them because they deserved it,” he says, for putting together a well-balanced team and coming up with the best ideas.

During the summer break, the team built a prototype of a satellite they hoped to launch into orbit, but some members seemed a little lacking in self-confidence.

That evaporated during a presentation at NASA’s annual Small Satellite Conference in Logan, Utah.

“The people at the conference just bowled them over,” Kitts says.

“They said (the idea and the prototype) were just fantastic.”

Enlightening Research

|

“They used the kind of stuff you can buy at Radio Shack.” |

The project consists of three satellites. The first will carry some sort of sensor to see if a tiny orbiter is viable for carrying small sensors into space.

The other two satellites will carry out a scientific experiment.

After they’re launched by the mother ship, the two will slowly drift apart. Each will carry a receiver to record radio waves in the ionosphere caused by lightning.

The ionosphere is a poorly understood region in Earth’s upper atmosphere, and electromagnetic disturbances there can wreak havoc on communication satellites.

The tiny satellites will “receive the same blast coming from the same stroke of lightning,” and transmit that data back to the ground, Kitts says. Since they’ll be separated, any differences in the signals will tell scientists something about the part of the ionosphere that the radio waves passed through.

Kitts sees it as a small start in what could be a major project consisting of a fleet of tiny satellites that could warn ground controllers of approaching disturbances that might damage other satellites.

That would be several years down the road and by then, the members of Santa

Clara’s team will be seasoned veterans in space design — and won’t have

to go to Radio Shack for parts.

![]()

Lee Dye’s column appears Wednesdays on

ABCNEWS.com.

http://204.202.137.111/sections/science/DyeHard/dye981216.html

Copyright ©1998 ABC News and Starwave Corporation.

All rights reserved.

This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or

redistributed in any form.

By Terry Costlow

EE Times

(10/11/99, 2:32 p.m. EST)

The task of designing some of the tiniest birds ever sent into space was tough by itself. But turning those designs into modules that can withstand the rigors of a space launch was no simpler.

"Everything is hand-built, the circuit boards were milled here, every board structure and every antenna was hand-fabricated by us," said Amy Slaughterbeck, one of the group's electrical engineers. "We actually soldered parts on boards many, many times. This was pretty much self-funded, so we had to do things ourselves." Undoubtedly, the group members will be big fans of outsourcing once they get into industry.

Overall, the women's senior project spanned 10 months. Ten busy months.

"Combined, I believe we spent around 5,380 hours in total, though that doesn't include a lot of the early work we did planning and meeting to talk about our progress and next steps," said Corina Hu, another EE. "Lots of the time, we spent 40 hours a week on the project. That fluctuated sometimes, like when we had finals, but I think we spent at least 20 hours per week per person on the project."

The picosatellites will fit into a larger satellite designed at Stanford University. A couple of months after the military does its work, the university's unit will be deployed, and it will then eject the smaller satellites. They will measure changes in the ionosphere.

When the Santa Clara students first got together and decided to submit a proposal to Stanford, they had no plans to limit their membership to women. But they had a combination of mechanical and electrical engineers and a computer science major who all knew one another, so they decided to link up. They named their team Artemis, after the Greek goddess of the moon. It wasn't just gender and the heavenly location that attracted them to that name.

"We really spent some time looking around on the Internet when we were thinking about naming our group," Slaughterbeck said. "Finally we voted on names. We picked Artemis because she wasn't only a feminine icon, she was known as a hunter, which was not a typical role for a woman at that time. We were atypical as satellite builders, so it fit."

Women make up only about 16 percent of all engineering graduates, according to the Society of Women Engineers, and the number of women in satellite design is even smaller. That got the Santa Clara students noticed. But it was the fact that the picosatellites are tinier than some experts said was possible that earned them respect.

The three satellites weigh a total of 611 grams and consume only 24 cubic inches of space. Two of the units house a 68HC11 processor with memory, gallium-arsenide solar cells and AA batteries, as well as sensors. Very low-frequency transmitters and receivers communicate with both the mother satellite and earth stations.

A third, less complex module simply broadcasts the Artemis Web site in Morse code. Ham radio operators who hear the code and check the site will realize they've been communicating with an orbiting satellite.

Sandwiching the demands of the project between classes, studying, part-time jobs and the desire for some downtime was never simple. "It started out as fun, but it came to a point when we got tired," said Theresa Kuhlman, a mechanical engineer. "A lot of things didn't work the way we thought they would, so we had to change things and sometimes do them over. We were all tired of it and it was a struggle, but we knew it was something that we had to deliver within a set time frame."

One of the group bailed out fairly early in the program. "We started out with seven of us, but right in the beginning, the first week of January, our computer science engineer made a personal decision to pursue another project," Slaughterbeck said. "No one else had her skills, so we had to get friends to help us."

As problems arose, team members worked together to keep each other motivated. Professors, upperclassmen, former students, associates at the Stanford lab and others supplied answers, suggestions and support.

Rubbing elbows with experts

One big motivational moment came when the team was invited to present a paper at a small-satellite conference. Getting away from the university and being around experts in the satellite industry was a heady experience.

"When we went to the small-satellite conference we had a very good time. We all got together and we were there for a few days," Slaughterbeck said. "We were unique, since we were about the only females there. We had a lot of notoriety, and that was a natural high for us. It really sparked us to work on the project."

The Artemis team built on uplifting events like the trip and kept their eyes on the final goal. Even though they were building more modules than other groups involved in the Stanford project, and building them with limited funds and time, they didn't let problems overcome them.

"We never had any doubts we would make it within the deadline," Hu said. "We built three satellites as students; the other picosatellites [on the mission] were not student-built. They were done by a radio team and some companies."

The lengthy effort was even something of a motivator for some of the team members, crystallizing career plans for a couple of Artemis engineers. One is now doing graduate work at an aerospace school in France. Another has started working for Lockheed. A third is focusing on communications and seriously considering zeroing in on satellite communications.

The remaining students are doing graduate work now. Some plan to trek to the launch, which was originally set for September. Even though they completed the Artemis project in May, when they all graduated, they still have a stake in the outcome. You couldn't spend all that time designing and building the satellites and not get emotionally involved. Even those who can't attend will pay attention.

"If it works, it will be very exciting. There will be a sense of completeness, of closure," Kuhlman said.

http://www.eetimes.com/story/OEG19991011S0038

Copyright © 2000 CMP Media Inc. All rights reserved.